I collected some additional information about this subject from the internet. The map as such is a piece of art but the enlargments of the map are very interesting as well.

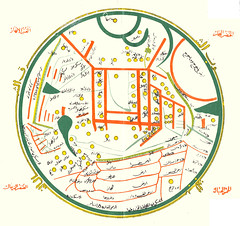

Qarakhanid Uyghur scholar Mahmud al-Kashgari compiled a "Compendium of the languages of the Turks" in the 11th century. The manuscript is illustrated with a "Turkocentric" world map, oriented with east (or rather, perhaps, the direction of midsummer sunrise) on top, centered on the ancient city of Balasagun in what is now Kyrgyzstan, showing the Caspian Sea to the north, and Iraq, Azerbaijan, Yemen and Egypt to the west, China and Japan to the east, Hindustan, Kashmir, Gog and Magog to the south. Conventional symbols are used throughout- blue lines for rivers, red lines for mountain ranges etc. The world is shown as encircled by the ocean.[15] The map is now kept at the Pera Museum in Istanbul.

Source: Wikipedia

*******

Mahmud Kashgari’s 11th C. Map of Turkic World

The above map appears in Mahmud Kashgar’s late 11th century Diwan Lugat at-Turk. According to the the 1982 Dankoff translation’s introduction, Kashgari was born near Issyk-kul into a family of the Qarakhanid dynasty. He traveled widely among the Turkic tribes of his time, and his map shows the locations of dialect groups. He split Turkic into two main dialect groups: the Turks and the Oghuz. He believed it necessary for non-Turkic Muslims to learn the language of the Turks.

"…every many of reason must attach himself to them, or else expose himself to their falling arrows. And there is no better way to approach them than by speaking their own tongue, thereby bending their ear, and inclining their heart."

…

"I heard from one of the trustworthy informants among the Imams of Bukhara, and from another Imam of the people of Nishapur: both of them reported the following tradition, and both had a chain of transmission going back to the Apostle of God, may God bless him and grant him peace. When he was speaking about the signs of the Hour and the trials of the end of Time, and he mentioned the emergence of the Oghuz Turks, he said: “Learn the tongue of the Turks, for their reign will be long.” Now if this Hadith is sound … then the learning it is a religious duty; and if it is not sound, still Wisdom demands it."

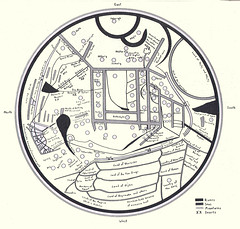

Below is another version of the map in English. Click on it for a much larger version. A version that has been rotated so that the top of the map is north can be found at strange maps.

A Key to some of the locations in the map

1. Bulgaria 2. Caspian Sea 3. Rus 4. Alexandria 5. Egypt 6. Tashkent 7. Japan (surrounded by water-the green semicircle 8. China-with water to the west 9. Balasaghun-the center of the world 10. Kashgar-Mahmud's birthplace 11. Samarkand 12. Iraq 13. Azerbaijan 14. Yemen (15-18 Africa) 15. East Somalia 16. East Sahara 17. Ethiopia 18. North Somalia (19-22 Indian subcontinent) 19. Indus 20. Hindustan 21. Ceylon and Adam's footprint 22. Kashmir 23. God and Magog 24. the world-encircling sea.

These and other locations and given in Albert Herrmann, "Die älteste türkische Weltkarte (1076 n. Chr.)," Imago Mundi I(1935)21-28.

The red mark on the south side of the map (21) identifies the location of the "footprint of Adam," Jebel Serandib, Adam's Peak, on the island of Ceylon, to which Adam was exiled after he was exiled from Paradise. Gog and Magog (23) are a nation and its ruler which represent an apocalyptic evil power, walled off from the world by a range of mountains.

These and other locations and given in Albert Herrmann, "Die älteste türkische Weltkarte (1076 n. Chr.)," Imago Mundi I(1935)21-28.

The red mark on the south side of the map (21) identifies the location of the "footprint of Adam," Jebel Serandib, Adam's Peak, on the island of Ceylon, to which Adam was exiled after he was exiled from Paradise. Gog and Magog (23) are a nation and its ruler which represent an apocalyptic evil power, walled off from the world by a range of mountains.